Over four hundred years ago, in 1619, the first law regarding cannabis was passed in the United States, when the Virginia Assembly required every farmer to grow hemp. At that time, hemp’s resiliency, simplicity to grow, and versatility made it perfect for the production of rope, sails, and clothing. Though domestic production of hemp diminished

after the Civil War with cotton textiles becoming more commonplace, cannabis remained a medicinal staple and was openly sold in pharmacies. Over a century later, in Massachusetts, individuals are now permitted to own a maximum of twelve cannabis plants, assuming there are multiple people over the age of twenty-one living in the home.

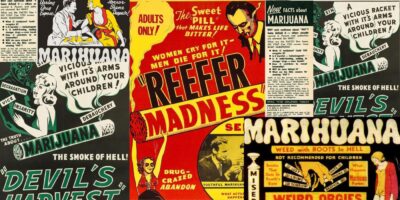

America’s relationship with cannabis has undergone many ups and downs since the passage of that first law in 1619. Dispensaries now allow consumers to purchase cannabis products that can help relieve ailments both physical and mental. Yet just a century ago, people mistakenly believed that cannabis could cause a host of detrimental effects, including mental instability and violent behavior. The true “Reefer Madness” is the journey cannabis has taken—and continues to take—through the legal system.

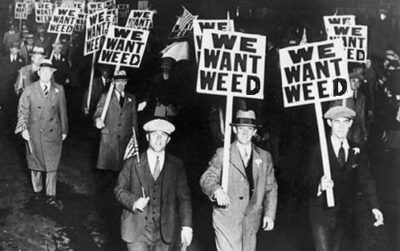

Despite the Virginia Assembly’s early enthusiasm for hemp, cannabis use in America waned after the Civil War years. That changed around 1910, when the Mexican Revolution led to a flood of refugees into the US. The newcomers brought recreational cannabis with them and, as a result, people’s conception of cannabis at that time was largely founded on fear and prejudice. The Great Depression didn’t help the plant’s reputation, either. Nationalists raised fears about Mexicans taking American jobs, which in turn increased public and governmental concern about the “Marijuana Menace.” As early as 1913, the Salt Lake Tribune, under the headline “Evil Mexican Plants that Drive You Insane,” reported that “marijuana make(s) the smoker wilder than a wild beast” and provided anecdotal evidence of average people becoming murderers after smoking cannabis.

Jumping onto this bandwagon of fear exploitation was one William Randolph Hearst, who controlled a journalism empire that dwarfed any modern media conglomerate. One of his papers reported that “Marihuana is a short cut to the insane asylum. Smoke marihuana cigarettes for a month and what was once your brain will be nothing but a storehouse for horrid specters.” In 1928, a Hearst paper reported that “marijuana was known in India as the ‘murder drug,’ it was common for a man to ‘catch up a knife and run through the streets, hacking and killing every one he [encountered].’” The article went on to claim one could grow enough cannabis in a window box to “drive the whole population of the United States stark, raving mad.”

Rampant racism also reared its ugly head in higher offices at the time. In 1930, Harry Anslinger, appointed by Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon (his wife’s uncle), became the first director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Anslinger, an avid supporter of Prohibition, had downplayed the dangers of cannabis before his appointment. Once appointed, however, he began a campaign based on racism and violence. He was quoted as saying, “There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the US, and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing, results from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and others.” The 1936 film Reefer Madness reflected echoed these themes, depicting cannabis as a substance that induced violence in men and sexual promiscuity in women. By 1931, twenty-nine states had outlawed cannabis.

In 1937, Congress drove the final nail into the coffin of legal cannabis when it passed the Marijuana Tax Act, which effectively criminalized marijuana outside of the medical and industrial fields. Meanwhile, the New York Academy of Medicine issued an extensive report, which fell on deaf ears, declaring that marijuana did not induce violence or insanity and did not lead to addiction or other drug use.

While recreational use of the plant remained illegal, during World War II, the US Department of Agriculture turned to hemp to produce marine cordage, parachutes, and other military gear. It launched a “Hemp for Victory” program and registered 375,000 taxable acres of hemp in the United States.

Yet the love affair didn’t last—in the 1950s, mandatory sentences for drug-related offenses were enacted federally. A decade later, in the 1960s, a cultural climate shift led to more lenient attitudes towards cannabis. Reports commissioned by Presidents Kennedy and Johnson once again found that marijuana use did not induce violence or lead to use of heavier drugs. The future of cannabis legality was looking brighter by 1970, when Congress repealed most of the mandatory penalties for drug-related offenses. But then President Richard Nixon enacted the Controlled Substance Act, or CSA, which labeled cannabis as a Schedule I drug. By CSA definition, cannabis had an unacceptable lack of safety, a high potential for abuse/addiction, and no accepted medical use in the United States. In 1972, the Shafer Commission, appointed by President Nixon at the direction of Congress, reviewed laws regarding cannabis and formally recommended that personal use should be decriminalized.

Nixon rejected the recommendation and even sought to discredit the Shafer Commission’s findings, though for his own purposes. As America later learned through the Nixon tapes, the president despised both African Americans and the antiwar movement. John Erlichman, a senior advisor to Nixon, was later quoted as saying “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.” However, despite presidential pressure, eleven states decriminalized cannabis throughout the 70s, and many others reduced their penalties.

Yet in 1976, public sentiment once again began to shift. Then a parent’s movement against cannabis led to the 1980s War on Drugs, and mandatory sentences were re-enacted by President Reagan. The “three strikes you’re out” policy required life sentences for repeat drug offenders. The War on Drugs continued under President George Bush in 1989. Thankfully, seven years later, California passed Proposition 215, which allowed for medical use of cannabis for patients with AIDS, cancer, and other serious painful diseases. The tension between federal laws that criminalize cannabis and state laws that permit it continues to this day.

Fueled by racism, fear, and even misguided nationalism, the journey of cannabis through the legal system has been nothing short of madness. From being abundantly available at any pharmacy to being classified as having no recognized health benefits, cannabis has become the most regulated substance on the market today. One can only hope that this review of its history can spark more awareness and aid full legalization of a plant that never deserved its harsh labeling. As I say when anyone asks me, “When do you think the daily allotment will be increased?” or, “When do you think it will be as easy to buy cannabis as it is to buy alcohol?”— keep voting, my friends.

Written by Bryan Burgwardt